Connections between marine conservation and GIS

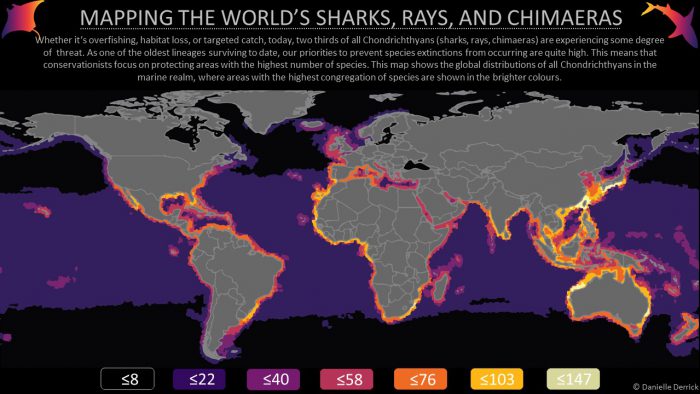

It’s fascinating to see the diverse world of ecology, conservation and marine sciences becoming enveloped in every expanding niche of spatial research. I am now more often seeing and reading the exciting new avenues that conservation and GIS are taking for species, ecosystems and countries alike. Conservation is a constant uphill battle and knowing where to focus our efforts is an even more difficult task. Amidst all the sad stories involving over-fishing, polluted waters, and endangered species, conservation can have some silver linings. Stories that display the remarkable recovery of humpback whales since being fished to the verge of extinction, increases in the implementation of marine protected areas, and sustainable fisheries becoming more and more prominent. Where my research comes in is somewhat abstract to the story I’ve been telling so far. I attempt to understand the evolutionary and ecological processes of species distributions in the marine realm. I use Chondrichthyes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras; hereafter referred to as sharks and rays) as my study system because one quarter of all sharks and rays are threatened just based on their body size and exposure to fisheries alone. A large part of my research helps us form baseline understandings of why species are where they are. However, sometimes my work can have conservation silver linings as well. To explain we have to start from the beginning…

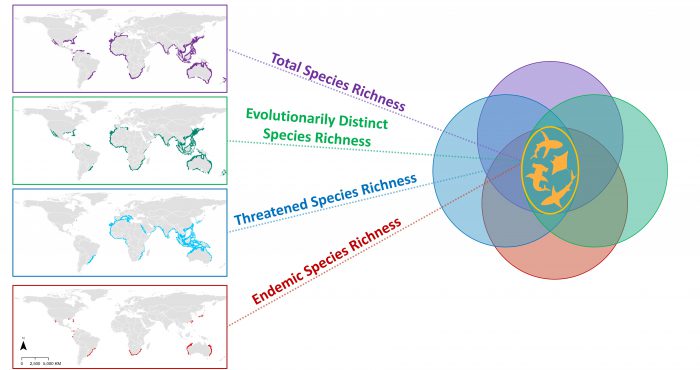

We tend to focus our conservation efforts on areas where we know there to be a high number of species, this is known as species richness. However, there are other measures that we can use when making conservation decisions. For example, we can focus on areas where there are a high number of threatened species, areas where species are known to only be found in a small number of locations (i.e., endemic), or areas where species encompass a large fraction of the evolutionary history of a lineage (i.e., evolutionarily distinct species). It can be hard to make the right conservation management decisions when both the overall goal is somewhat unclear, and the options are endless. The 2020 Aichi biodiversity targets to conserve 10% of coastal and marine areas has just passed, and the 2030 targets aim to protect 30% of areas on both land and sea. This offers me a unique opportunity to contribute to the 2030 agenda. I can do so by identifying areas where we can protect a combination of the greatest number of species for each metric of species richness, threatened, endemic, and evolutionary distinct species. That is, we can determine where these areas of overlap occur in the spatial environment. Furthermore, we can explore the effect of spatial resolution on our ability to identify areas of congruency.

In short (you can read the poster linked below for full details), I was able to identify that 2% (936,469 km2) of areas were congruent between all four metrics (richness, endemicity, threat, and evolutionarily distinct). While increasing the spatial resolution will inevitably capture a greater proportion of biodiversity metrics, the extent at which this occurs remains relatively low and locations of congruency shift as resolution changes. Hence, understanding how species distributions change across spatial extents can provide insight into the strength that different local, environmental, and evolutionary drivers have on the distributional differences in biodiversity metrics. Furthermore, focusing conservation efforts on species-rich areas are more than likely inadvertently overlooking other desirable dimensions of biodiversity, such as endemicity or evolutionary distinctiveness. The silver lining here is that these identified areas of congruency highlight the lack of spatial distributional similarities between biodiversity metrics and could provide an informative perspective on where management could focus their efforts for the conservation of shark and ray biodiversity, especially in preparation for the 2030 Kunming targets.

Overall, I have been enjoying being able to see GIS having a larger impact on conservation management decisions, ultimately providing more information and data to make the big decisions that are always so tough to call. This research helped me achieve Simon Fraser University’s Higher Education GIS Scholarship in March of 2020. You can see the poster I made for it at the bottom of this blog post and feel free to contact me with any questions or inquiries. This post is just the tip of the iceberg for this project and I am sure I will be staying headstrong in the direction of marine conservation for the foreseeable future.

SFU Higher Education Scholarship Poster: